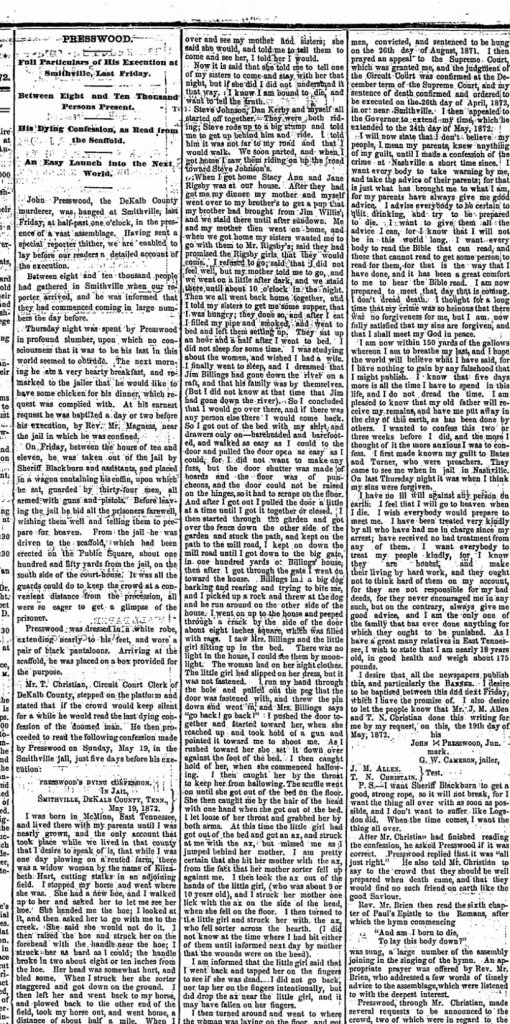

Murder on the Caney Fork: The Trial and Execution of John Preswood for the Death of Rachel Billings, 1871–1872

In the winter of 1871, the quiet communities along the Caney Fork River in DeKalb County, Tennessee, were shaken by one of the most brutal crimes in the county’s history. Rachel H. Billings, wife of James Billings and mother to young Inez Certain, was murdered in her home while her husband was away working on the river. Inez was assaulted in the same attack. Within hours, suspicion fell on a neighbor—eighteen-year-old John Preswood (also recorded as Presswood)—whose red hair and proximity to the scene made him memorable to witnesses. The subsequent trial, stretching through 1871 and ending in Preswood’s execution in May 1872, reveals much about 19th-century rural justice, community testimony, and the standards of evidence at the time.

The Crime

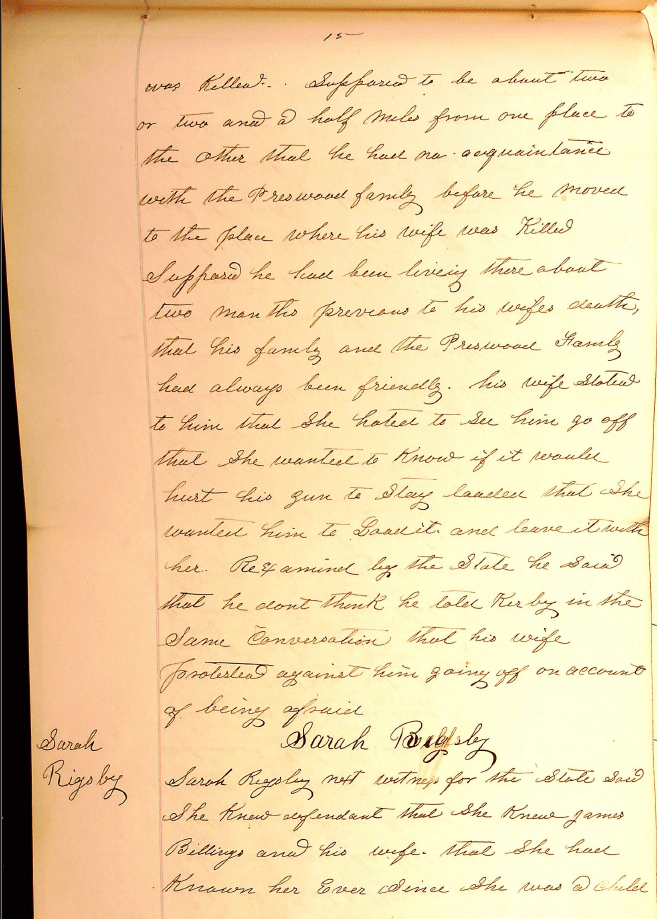

On Sunday night, January 29, 1871, Rachel Billings and her children were at home, about a quarter to half a mile from the Preswood residence. James Billings was away, working as a hireling on a rafting crew. The next morning, twelve-year-old Inez went for help. Neighbor Sarah Rigsby testified:

“The little girl (Inez) came near witness’s house on Monday morning… she said that a man came to their house about midnight and had killed her mother… said it was a red-headed man in answer to a question witness asked as to what sort of a man it was.”

Rigsby hurried to the Billings house, where she found Rachel dead on the floor, her “legs… scratched and bloody and her knees bruised,” wearing only a nightcap and shimmy. She noticed “the bloody prints of a right hand on the floor near the body” and “a chopping axe lying on the floor under the bed… the handle and the pole of the axe was bloody.” The water bucket in the room “looked red… like it was saturated with blood.”

Identification and Accusations

The most direct accusation came from Inez herself, who testified in court after being judged competent by the judge. In a series of questions, she recounted:

“He poked his hand through the crack and unpinned the door… jerked Mother out of the bed… I got the axe out from under the bed and hit him with it… he jerked the axe out of my hand and struck me on the head… he hit her on the head with the axe—three [blows]… Who was it killed your mother?

John Preswood… After your mother was knocked down did you see him lying down with her? Yes sir… She was groaning… He was barefooted… He washed his hands… in the water bucket.”

Other witnesses confirmed Inez had named Preswood on the morning after the murder. Lucinda Billings testified that Inez told her “it was John Preswood… he came there about midnight… pulled out [the door] pin… jerked Mother out of bed… knocked Mother in the head… stayed a little while… washed his hands… and went off.”

This testimony, however, became a major legal issue. The judge later instructed the jury to disregard Inez’s out-of-court statements to Rigsby and Billings because they were hearsay—what the defense called “illegal evidence.” The court acknowledged:

“…had objection been made at the time, said statements would not have been permitted to go to the jury.”

The damage was done, however—the jury had already heard the account.

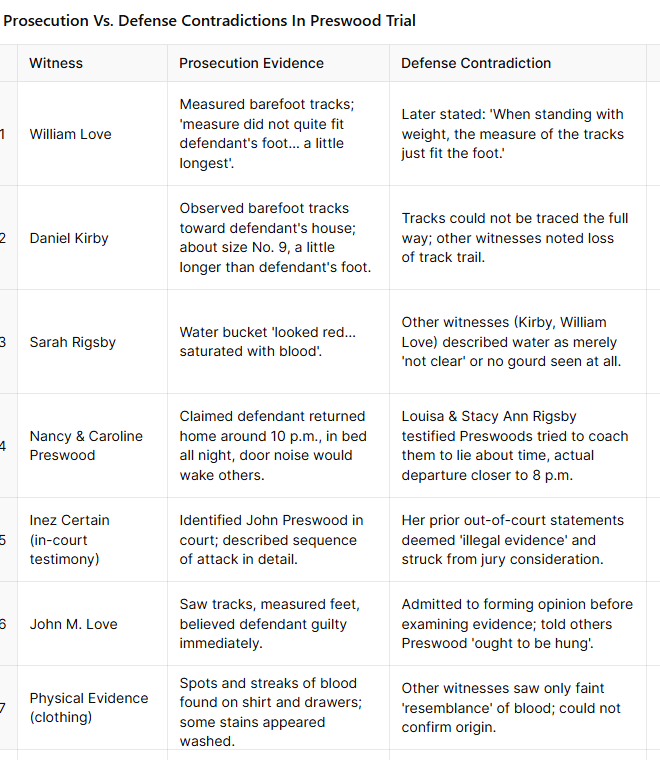

Physical Evidence — and Conflicting Descriptions

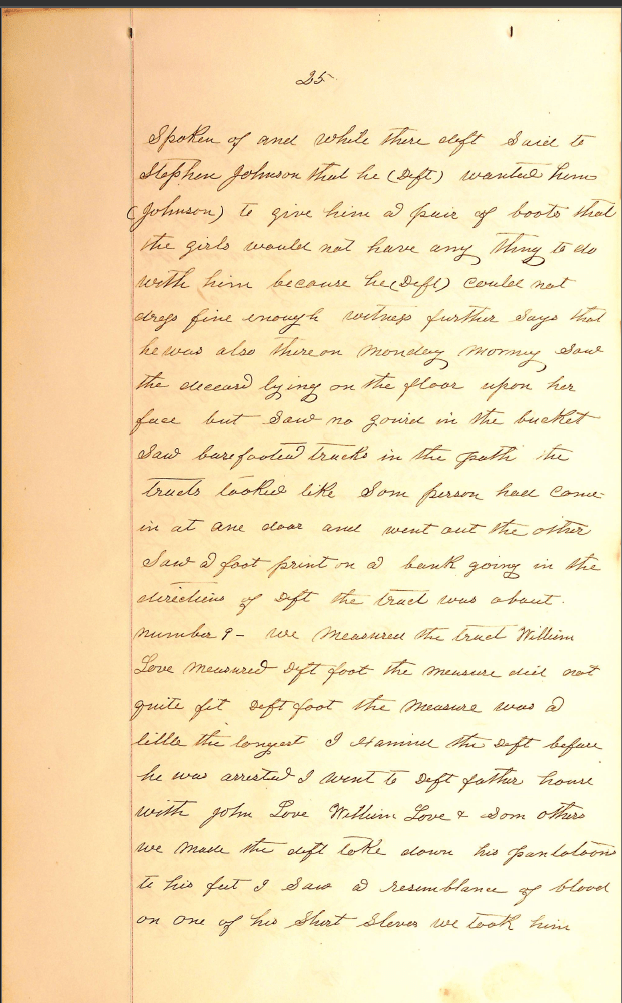

Several men examined the scene and Preswood’s person on Monday morning. Daniel Kirby testified to “barefooted tracks in the path… about Number 9” shoe size, with measurements “a little longer” than Preswood’s foot. He also observed “bloody scratches on the prisoner’s feet and ankles… looked like briar scratches… the scratches had dried over.”

William Love, who participated in the examination, gave two differing descriptions of how the tracks compared to Preswood’s foot size. In one account:

“Love measured Deft foot… the measure did not quite fit Deft foot… the measure was a little longest.”

But elsewhere in his testimony, after describing having Preswood set his foot forward while seated, he stated:

“The measure was a little longer than his foot but when he stood up and placed his weight on his foot the measure of the tracts just fit the foot.”

The difference between “did not quite fit” and “just fit” was never resolved in court, but it illustrates how track measurement—one of the few physical comparisons available—was as much subjective interpretation as science.

Other physical details were similarly inconsistent. For example, some witnesses swore they saw clear stains on Preswood’s shirt and drawers (“a plain spot of blood on the hip… plain specks on the bosom”), while others described these as mere “resemblances” of blood, faint and possibly washed.

Community Opinions and Prejudgment

John M. Love admitted to telling others immediately after hearing of the murder that “John Preswood was the man… and he ought to be hung for it,” acknowledging that this opinion was formed before any formal examination of evidence. He also admitted telling people during the term of court that the judge ought to summon a jury “and have Deft hung.”

This prejudgment mattered because the defence had already objected that nine jurors admitted under oath to having formed an opinion about Preswood’s guilt from “neighbourhood chat and general rumour.” The judge allowed them to serve anyway, over the defence’s objection.

The Alibi — and Its Cracks

Preswood’s defence rested heavily on an alibi provided by his family. His father, John Preswood Sr., testified that John returned home from visiting the Rigsbys around 10 p.m., “went to bed in a few minutes… was at home all night… complaining of his head… if he had gone out the door, I would have heard it scrape on the puncheons.”

His sisters Nancy and Caroline supported this timeline, claiming they were with him until late evening and that he slept in the same room. Yet here, too, contradictions emerged. In her statement before the Justice of the Peace, Nancy allegedly placed their departure from Rigsby’s between 10 and 11 p.m.. Still, Louisa and Stacy Ann Rigsby testified that Nancy and her mother had tried to persuade them to swear to that time, “and that would clear John,” even though the actual departure was around 8 p.m.

Adding to the credibility damage, witness Louisa Rigsby swore that Nancy “did swear it… it was not that way,” and Stacy Ann echoed, “they did swear it… It was not correct.”

Contradictions in the Scene Description

Even the condition of the crime scene was described differently.

Some, like Sarah Rigsby, recalled the water bucket “looked red… saturated with blood.”

Others, such as Daniel Kirby, testified they saw “no gourd in the bucket” at all, while William Love described the water as merely “not clear.”

Similarly, footprints were variously said to have been traceable all the way toward Preswood’s home (Kirby) or disappearing partway along the path (John M. Love), with the latter blaming gravel for the loss of the trail.

Jury Charge and Verdict

Judge Samuel M. Fite gave the jury a lengthy instruction on the law of homicide, explaining degrees of murder, manslaughter, and justifiable homicide. He told them they must be “clearly satisfied” of guilt and should weigh the testimony of a “child of tender years” like Inez with care, considering her age, intelligence, and consistency.

Despite the conflicting measurements, variable scene descriptions, hearsay controversies, and family testimony disputes, the jury deliberated and returned with a verdict:

“…guilty of the murder of Rachel H. Billings in the first degree… no mitigating circumstances.”

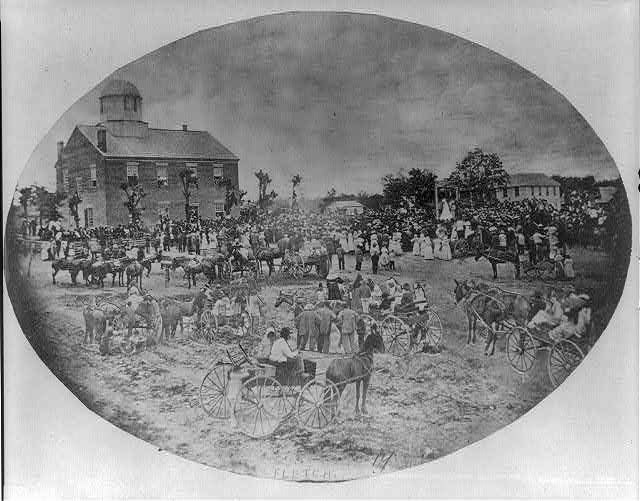

Preswood’s motions for a new trial and arrest of judgment were denied. He was sentenced to be hanged within one mile of the courthouse in Smithville.

Execution and Aftermath

John Preswood was executed on May 24, 1872. Reverend Jerry W. Cullom preached at his funeral. The case left an enduring mark on local memory, not only for the violence of the crime but for the legal issues it raised—primarily the handling of hearsay, the competency of child witnesses, and the question of juror impartiality in a small rural community.

Historical Reflections

From a modern perspective, this trial presents an uneasy mix of circumstantial and direct evidence, much of it contested:

Physical measurement contradictions weakened the forensic link between Preswood and the tracks.

Conflicting crime scene details (condition of the bucket, clarity of the footprints) showed how observation could vary even among people standing in the same room.

Witness credibility attacks—including claims of coaching and fabricated timelines—undermined the defense’s alibi.

Juror bias was admitted openly, yet tolerated under the standards of the time.

Ultimately, the verdict suggests that in Reconstruction-era rural Tennessee, a strong communal belief in guilt, bolstered by a child’s in-court identification, could outweigh inconsistencies that might prove fatal to a case today.

If you wish to see the court documents, or read my transcription it can be found here: WikiTree Space for John Presswood Trial

I have tried a few times to find a record of the assault he made on another woman before the Rachel Billings attack, as it may both show a pattern and be what prompted their move to the area near DeKalb.

As a note, now that we believe we have the burial location of Rachel Billings, a Find A Grave Memorial has been created for her, and on the list is to see if we can raise the funds for a tombstone, even a small one for her, as to my knowledge, she does not have one.

Following this will be an article on the Death Penalty and minors, which will be a few weeks away; this one has been several months in the making.